Cante jondo, machinic sounds interrogates this dialectic situated on a periphery by focusing on artists whose work is linked to music, sound, and the concept of the machine. In the pieces selected, and the underlying curatorial discourse, there is resistance to the oblivion of a unique cultural heritage while simultaneously an openness to cross-pollination by new artistic languages and tendencies, and a shunning of the empty shows of virtuosity and marketing inherent in much contemporary art practice. As such, the project aligns itself with the art historian and Reina Sofía Museum director Manuel Borja-Villel’s defense of the vernacular, of that which is “situated” and “minor;” and with Michel Foucault’s concept of “subjugated knowledge,” understood as that which is located outside of institutions and academia. This vindication is interpreted here as a possible means of emancipation from a homogeneous global aesthetic in which interdisciplinarity has become the norm.

This is a kind of return to Machado’s idea of the “songmaking machine” that creates “mechanical coplas” as an invocation of the hybrid discourse that brings together modernity and tradition, and converts the exhibition space in a place of ritual that welcomes such diverse elements as flamenco, machinic devices, electronic beats, and the idea of the algorithm.

Two of the historical nexuses in dialogue with the artworks are, on one hand, a copy of Juan de Mairena, a foundational text and one of the origins of the project; and on the other, the film Aguaespejo granadino [Water-Mirror of Granada] by José Val del Omar, part of his Elementary Triptych of Spain, which highlights the artistic side of the concept of the madcap machine rooted in Andalusian popular culture.

Both of these points of reference combine elements of machinic modernity and popular tradition. In the case of Antonio Machado, he employs poetical lyricism, while Val de Omar uses experimentation and the invention of sound and visual techniques and devices.

Palabra en masa: amarra (2021) forms part of the project Encyclolalia, in which Alegría and Piñero investigate the phenomenology of speech. This is an instrument that produces and modulates sound through reed whistles. A systematized process of gestures carried out by the sculpture create the word ‘amarra’ in a chorus of five voices. This piece was produced with the support of the Fundación Rafael Botí.

Modulador vocálico dinámico (2017) forms part of the project Encyclolalia, in which Alegría and Piñero investigate the phenomenology of speech. The modulating forms of “e”, “i”, “o” and “u”, are sectioned horizontally at half their height. As the vacuum bellows, the forms open up, forming a choir that derives in the sound “a”.

Holy Thriller (2011) is short film that combines pop culture and religious solemnity to offer a new view of some of the myths and symbols that construct the Spanish national identity. Holy Thriller depicts Michael Jackson as a pop martyr, in this sacro-pop cover of one of his most famous songs by a traditional Holy Week band. This hilarious video by multimedia artist and activist María Cañas is a mash-up of the hysterical fan phenomenon of popular culture and the solemn displays of religious passion at Easter, while highlighting how both of these performances, with their similarities and differences, immerse their respective audiences in collective ecstasy.

Al compás de la marabunta or Semana Santa, ese trabajo de hormigas, also by María Cañas, explores the animal essence of believers as illustrated by their fervor during religious processions. Using a satirical analogy, we see a mob of tiny ants who anxiously push a little wooden stick, all to the sound of the bands of traditional Andalusian music, the campanilleros, a rhythm that marks the pace of the swarm of the devout.

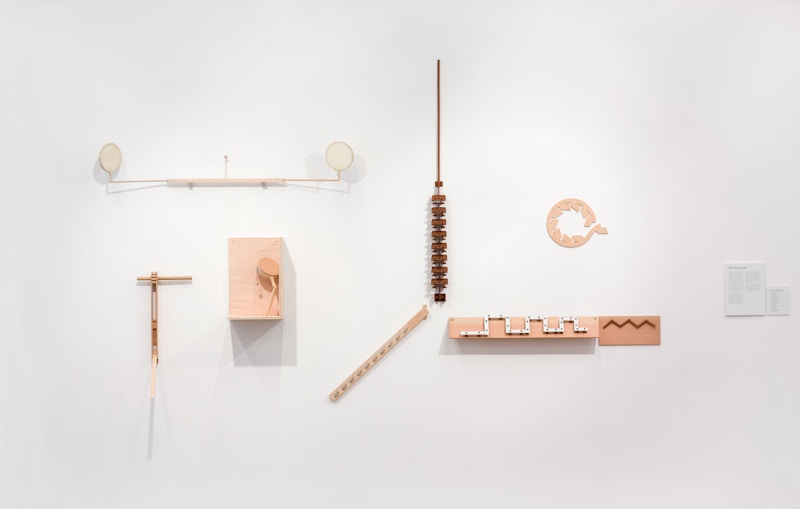

With the brevity typical of proverbs, Todo es nada lo de este mundo si no se endereça al segundo, by José Miguel Pereñíguez, reflects on objects’ capacity to ‘be straight’, a property that can determine the ability of things of this world to be or not to be. From this concept emerges a series of very elemental sculptures that, in various ways, interrogate this idea of ‘rectitude’ or lack thereof. Pereñíguez wants to reveal the paradoxes and absurdities found in the dynamic state of these objects. Most of the pieces in the series are also musical instruments, although their sound function is, in this case, not an actual one but an imagined one. The sound would result from some sort of movement produced in or with certain parts of these objects. Assigning a sound dimension to these works is yet another way to make the viewer visualize, even at rest, how any and every object is included within a web of actions and trajectories that can significantly alter their nature and their context.

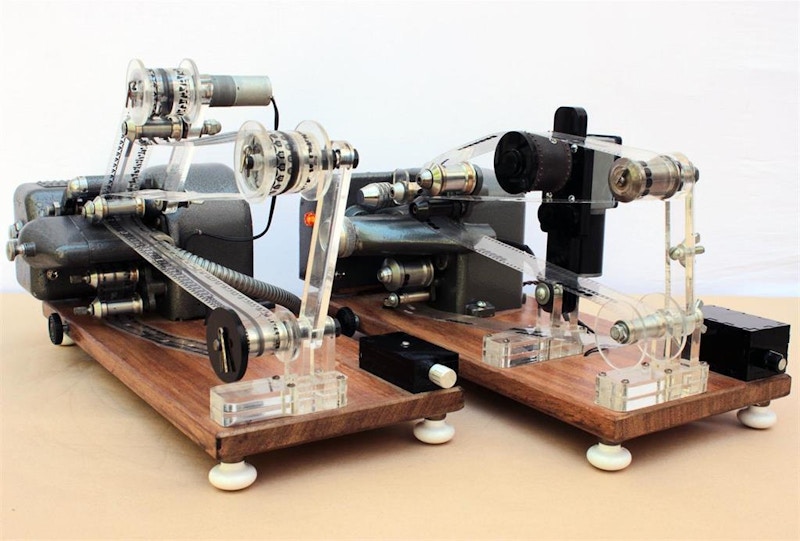

Phanoptic Readers (2020), by Enrique del Castillo, consists of two optical readers created by the artist himself that play two films without emulsion, turning celluloid into music compositions. The readers transform the light into sound and, since the films move at different speeds, they create a sound composition that is constantly changing.

The experience of perceiving colors as a colorblind in a browser environment is reproduced in the video Romance sonámbulo daltónico, a work by Los Dalton collective (Miguel Fructuoso, María Sánchez and Miguel Ángel Tornero), using the Sim Daltonism application. The Google searches are drawn from the poem Romance sonámbulo by Federico García Lorca. The results are gathered into an image bank, creating a universal iconography determined by Google’s own code that calls into question the conventions of both color and stereotype.

Afinar un cuerpo and Hacedores (2019), by Cristina Mejías, are part of Boca y hueso, a project that focuses on the figure of the artisanal maker of flamenco guitars. Unlike other standardized string instruments, flamenco guitars emerged as a tool of the troubadour or oral storyteller in taverns and traditional bodegas, and their construction continues to often be knowledge passed down from master to master. Their voices give shape to the wood. In this work, Cristina Mejías questions the strict methods of imparting history through a linear timeline and instead uses other, more intimate narratives, in this case sharing processes and studying the craft of her luthier brother, who in turn apprenticed under the master guitar-maker Rafael López Porras, who died in Cádiz in 2012. This experience allows her, through her artistic investigation, to carry out this artisanal practice and be another link in the chain of transmission and learning of these traditional guitar-making skills.