Until quite recently, the office was a space devoted exclusively to work; now that almost anachronistic idea has mutated: work has escaped those demarcated confines and invaded every aspect of life. Work no longer begins or ends in the office. Actually, it never ends at all, it has become omnipresent, expanding to fill all available time and space. The acceleration of capitalist logic and overproduction have led to the blurring of borders between the space and time devoted to work and the space and time devoted to rest and leisure. Office brings together artworks that reflect on the complexity of meaning in today’s concept of work –exacerbated by the multiple layers of meaning added by the current pandemic.

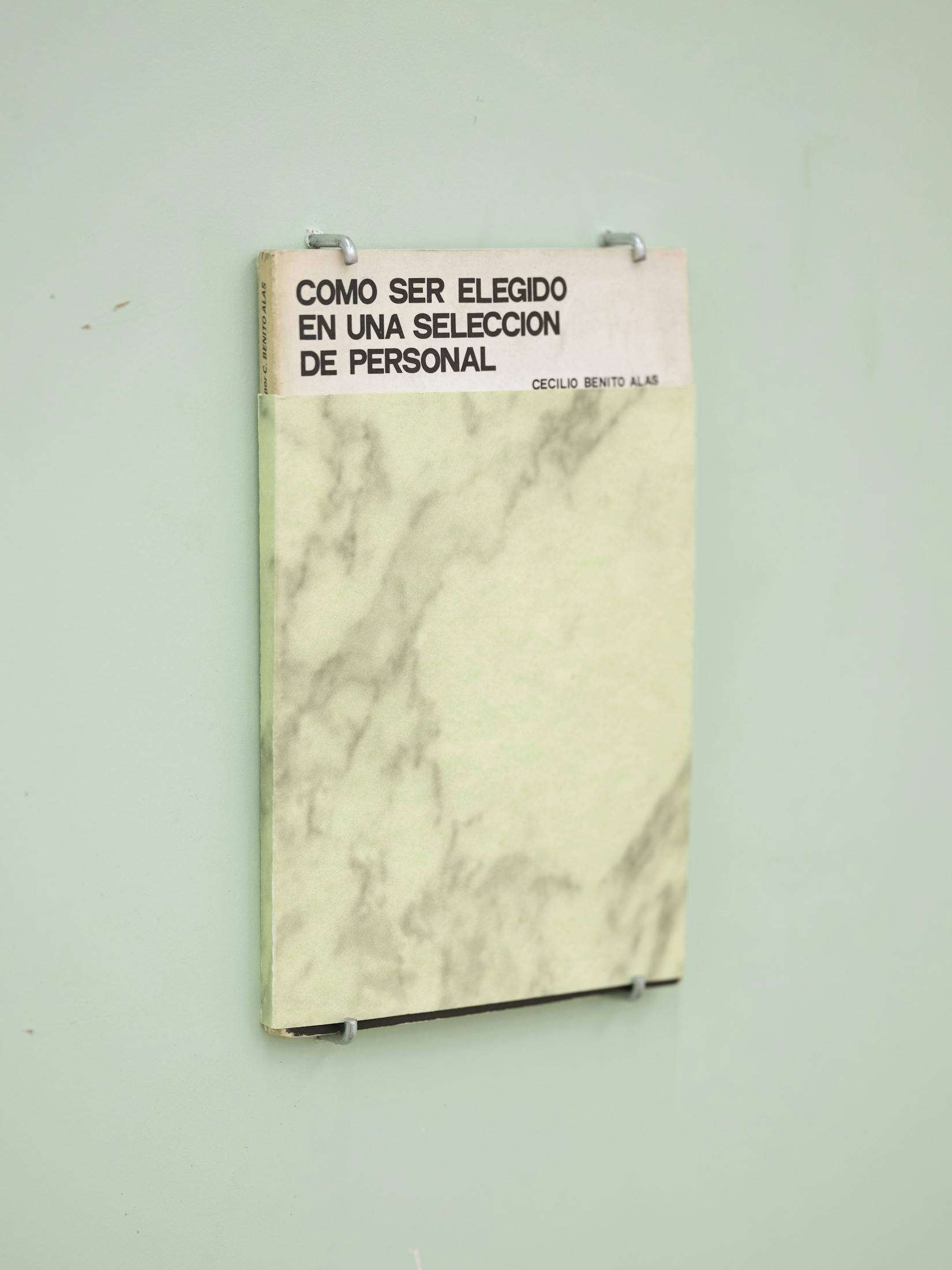

Modified copies of a test on personnel selection. In each of them, Alcaide responds by pretending to be one of the five bosses he has had. Printing and graphite